This special exhibition was first exhibited in National Taiwan Museum from June 26, 2018 to August 18, 2019. This year, the curatorial team collaborates with experts of the micropalaeontological circle in fine adjustment, and specimens of Taiwan collected by National Museum of Natural Science are added to make this special exhibition more connected to local visitors.

Microfossils are biological remains preserved after the death of microorganisms. This exhibition demonstrates four distinct groups of microfossils: foraminifera, coccolithophores, diatoms and radiolaria. Through the combination of modern technique and aesthetic, these microscopic creatures that are hard to discernible by the naked eye show astonishing variations of size and shape. That each individual is unique in its originality, geometry, and architecture leaves us to be deeply awed by the natural wonders.

The main theme can also be traced back to the 19th century to highlight major achievements of micropaleontology in Europe. By using scientific equipment and literatures that demonstrate the merits of these studies, we can grasp a glimpse of Victorian naturalists’ perception of the exquisite beauty. The geological implications of microfossils in Taiwan are showcased chronologically over the 20th century. Nowadays, microfossils can help us to have a better understanding of environmental variations in the deep past, the role these tiny organisms played in global climate change can also be contemplated.

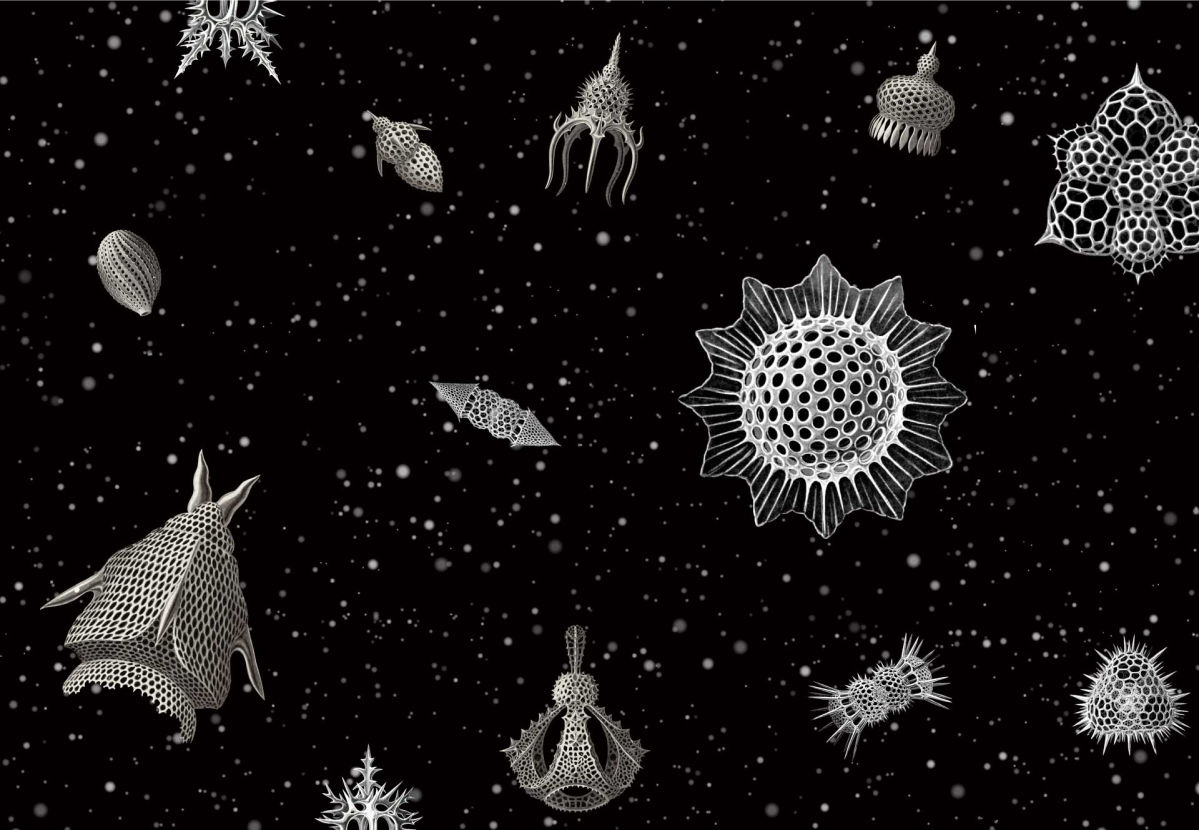

The vast ocean is the inner space of Earth. Hidden in the deep ocean sediments are microfossils with size as little as dust. Many of these hardly discernible creatures once lived floating in the sunlit shallow waters, and settled down to the seabed after the end of their life, joining those benthos lived at the bottom of the ocean for generations. Under the microscope, the shells and skeletons of microfossils show infinite variations of organic form. Among all, foraminifera, radiolaria, diatoms and coccolithophores are distinct in their exquisite beauty. That each individual is unique in its originality, geometry, and architecture leaves us to be deeply awed by the natural wonders.

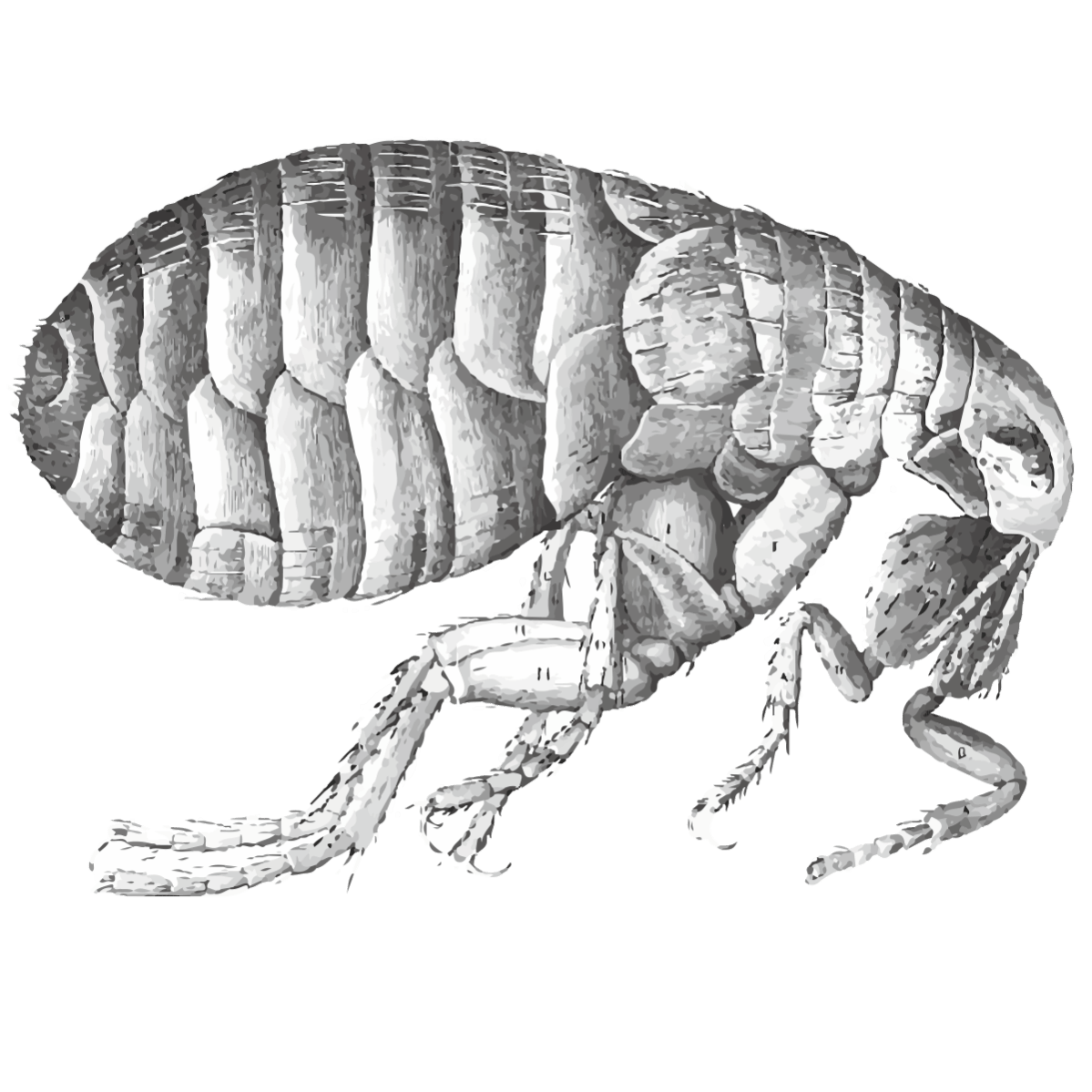

As early as the invention of the microscope in the 17th century, the first published illustration of foraminifera was documented from the text of the Micrographia by Robert Hooke. Anthonie van Leeuwenhoek had described the observations of diatoms using single lens microscope of even greater magnifying power. Through the scientific illustration of engraving prints, the impressive images that human being encountered the microscopic world can still be seen intact. These magnified engravings demonstrate that the tiny creatures seem vividly on paper with delicate touches, seemingly realistic and marvelous simultaneously. Through the collaboration of naturalists, painters and engravers, everyone can be inspired by the exquisite beauty of the prints.

The microfossil studies of Taiwan began with the geological surveys during the Japanese-ruled period. In 1899, Bunjiro Koto and Shigeyasu Tokunaga collected fossils from the northern Taiwan and sent them to the British scholars Bullen Newton and Richard Holland for research. In 1900, they published fossil content in limestone slides by microscopic examination, identifying foraminifera species including Lepidocyclina verbeeki, Gypsina, Miliolina, Pulvinulina, Globigerina, etc. This was the earliest report on Taiwanese microfossils documented in the literature. Geological investigation had gradually been extended to the whole island since then. The large foraminifera were the major dating tools as they were relatively easy to preserve and determine, and could provide important base to determine the age of rock formations. After 1945, the Central Geological Survey and Petroleum Exploration and Research Institute were established. The applications of small foraminifera and calcareous nannofossils were developed and carried out subsequently. It has since got a deeper insight of the geological past of Taiwan Island.

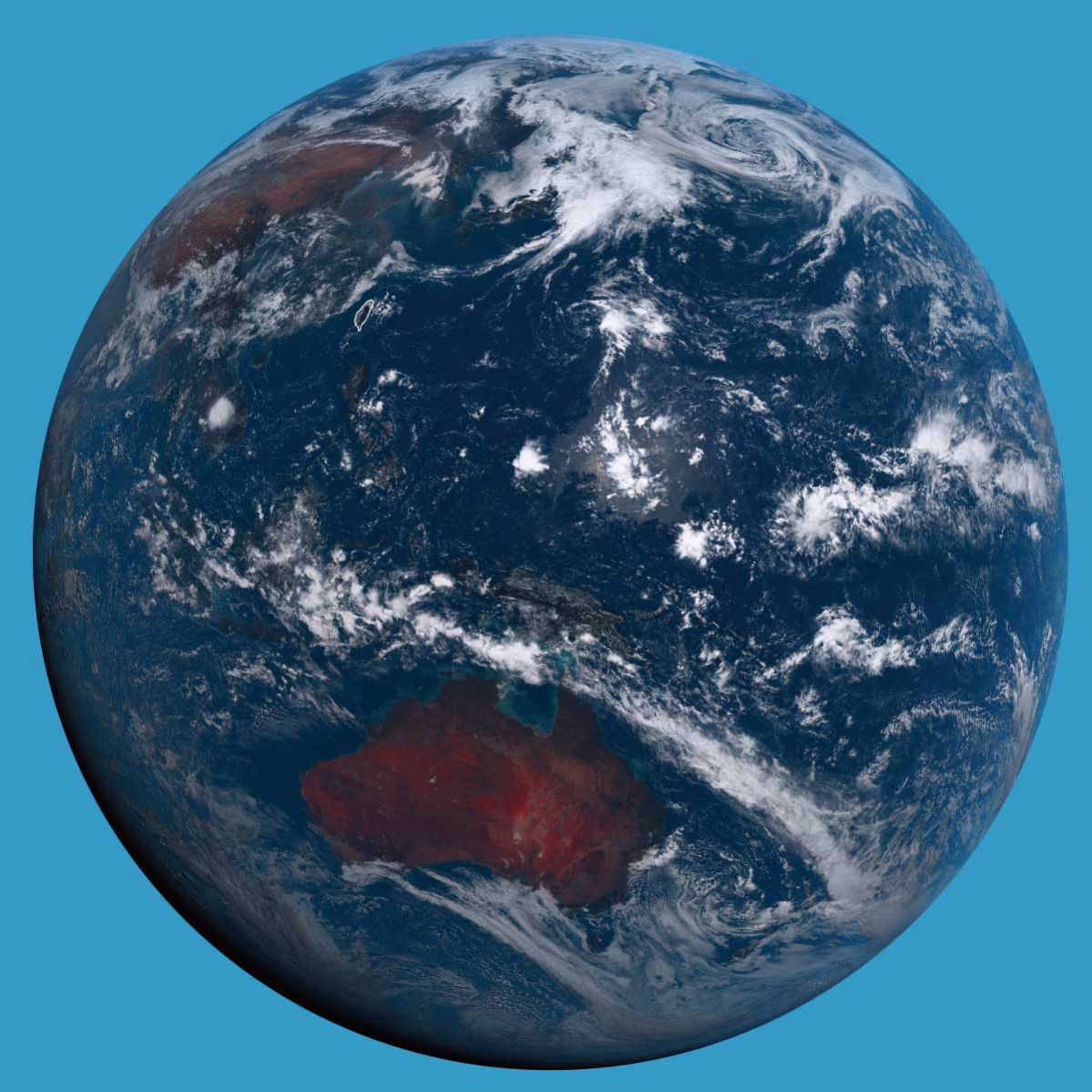

Diatoms and coccolithophores are two major primary producers of the trophic pyramid in marine ecology. They play an important role in regulating the global climate system, working like a thermostat to maintain the stability of Earth’s temperature. In contrast, the environmental disturbance by human activities has generated all kinds of marine civilization diseases. For example, ocean acidification makes organisms such as foraminifera and coccolithophores more difficult for calcification to build carbonate shells. The continuing accumulation of microplastics is widespread over the ocean, and the ubiquitous invader is laborious to clear away from the plankton world. On the eve of the global population breaking through the 8 billion mark, everyone should reassess human interference with life and environment under a macroscopic view of Earth’s system.

The 2nd Exhibition Gallery

Dec.30, 2020

V

Jun.27, 2021

Copyright by National Museum of Natural Science.